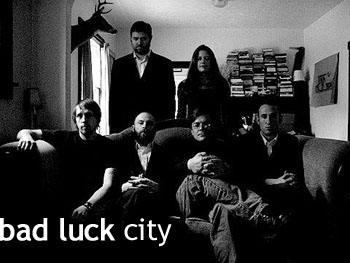

The great German thinker Friedrich Nietzsche believed that music was the only vehicle with enough horsepower to pick up where words leave off. Certainly, since antiquity words and music have swam in the same waters, sometimes swimming laps over one another – but for the most part written language has remained only a strong arm and lifelong ally to the land of music. This, when music is, in so many ways, literary. This, when song is story. And story, is song. Somewhere in these swampy waters, where words and music swim secretly under the coyote moon together, there is a place called Bad Luck City. I like the idea of a sound filling an entire room for an hour at a time. I like the idea of music transporting me: To a place. To a space, as though the front door of a venue is a wormhole. For this reason, the life-size act of Bad Luck City (Dameon Merkl, vocals; Greg Kammerer, guitar; Josh Perry, guitar; Jeremy Ziehe, bass; Kelly O'Dea, violin; Andrew Warner, drums) is aptly named. You walk into Bad Luck City, it doesn’t walk into you. As when you arrive at any gate, when you are standing in front of Bad Luck City, you are aware that you have arrived, somewhere. Standing in a room with the band and there’s a couple things that will immediately overwhelm you: the band’s large, spooky sound; O’Dea’s violin playing; and most certainly, Dameon Merkl – his presence, his click and teething pace on the stage along with his broken man’s cadence and literary lyrics. In large part, Bad Luck City is literary in the same way you would say that Dameon Merkl is the band’s vocalist. Because really, you wouldn’t say that he is the band’s lead singer. Merkl doesn’t sing. He moans and mulls over his words in that hushed, precise kind of way that a man contemplates a monumental manipulation. Instead you’ll find the music’s song and singer in the violin that Kelly O’Dea cradles. O’Dea’s strings drive the melodic charge that the boys behind push, gaiting through the swampy lands outside Bad Luck City limits. Even when the sun is in the skies, Bad Luck City sits in a mercurial and dark basin. In the middle of every where and nowhere, it has big, naked, open spaces surrounding the haunted buildings of Main Street. The deputy painters of this landscape are the guitars and drums. But like any city, this city is defined by its people, the stories of their lives. And those stories are told by O’Dea’s violin and Merkl’s words. Some of these stories are of a man sitting atop the floorboards where he buries the dead, counting his trespasses and crimes. “In a city of the dead, a living man must find a private tomb”, Merkl says. Some of these stories center around the namesake of Bad Luck’s current album, Adelaide: a horse whose legs break in a race. At the finish line, Adelaide is injected with death and driven away after “the crowd moaned its sullen serenade”. Both Merkl’s presence and words serve as the band’s sixth instrument. As a writer, his aptitude for story is strong, as are his cadence and pacing. Ultimately, Merkl is a writer, reciting his tales verbally. In “Bones” Merkl writes, “There are seven places to hide your bones upstairs/Although I doubt anyone would notice or really even care/I’ve seen the best of men swallowed by the ground”. In his despairing “The Widow of Frances Colver”, the weak-hearted widow writes, “But somewhere I read ‘Let the dead eat the dead’/And let us broken wrecks dance drunkenly at the edge”. With six people in a band, and most notably two guitars – things could get muddy in Bad Luck City. However, Greg Kammerer and Josh Perry’s twelve strings of texture are predicated more on the idea of a conversation than a riff factory. And for this, the citizens of the town have been blessed with open spaces to run when the lights go down over the hills and witchy streams. In Bad Luck City you will find a grand articulation of their blessing as a unit, as a town: here, the idea of conversation drives the horses of dialogue – between the guitars, O’Dea’s singing violin, Ziehe’s basslines and Warner’s drums. And where that conversation could turn into something rote, Warner is at all times the conductor of their county trains – pushing the band into uncomfortable dynamics, the holy provenance to a grounded and fluid flow of dialogue. While Bad Luck City hits many of the blackened, minor keys that some of their Queen City predecessors have struck – I would not push them into that americana, roots kind of company. Instead, what Bad Luck City has managed to create is something particularly fresh, as clean as fortune’s backside can be. The proof is in the live show behind the wormhole door. The proof is in the dead horse and her recordings. The proof is in the caveat I think I read on the city’s gates – the first lines of Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf: “For Madmen Only”. If you’re ready for a story, pay your dues and walk through the gates of Bad Luck City. For more of the City’s dark past, as well as their lighted, zenith future: www.myspace.com/badluckcity. |