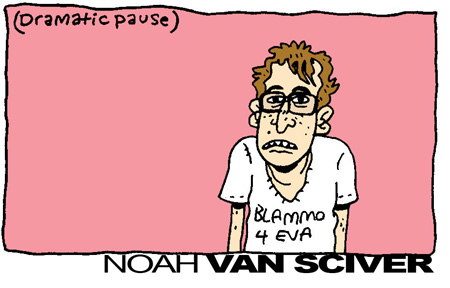

{enter gallery above} if you’re going to try, go all the way. otherwise, don’t even start. if you’re going to try, go all the way. this could mean losing girlfriends, wives, relatives, jobs and maybe your mind. In a world where everybody wants to be a superhero, Noah Van Sciver just wants to be himself. A rare breed, Van Sciver is a Denver cartoonist. In a world where drawing comics mostly means that you (want to) work for Marvel, Van Sciver is also another kind of minority, an Argonaut of sorts – for he is one of the few that draws underground comics. You can find Van Sciver’s work in Westword – he is the author and artist of “4 Questions” in the Backbeat music section and he also has his own underground comic, “Blammo”, which is published in town by Kilgore. But ask anybody in Denver if they have ever heard of Van Sciver or if they have ever even met a cartoonist apart from the caricature artist below the roller coasters at Lakeside. A little unsure of himself and a little uncertain about his time in space, Van Sciver is one part self-conscious and two-thirds confident. His laughter is like a wall or a segue or a push away from something too personal. And while you can feel that laughing wind of encouragement, for you to keep your distance, oddly-enough: Every story that Van Sciver draws is a cartoon about his life. Every character is a little bit of him. While I know that he is not interested in drawing for Marvel or anybody else that doesn’t share his name, at the end of the day I’m not so sure Noah Van Sciver doesn’t see himself as the hero of his own life: discomforted, paralyzed, humorous on account of folly and, alone. go all the way. it could mean not eating for 3 or 4 days. it could mean freezing on a park bench. it could mean jail, it could mean derision, mockery, isolation. isolation is the gift, all the others are a test of your endurance, of how much you really want to do it. and you’ll do it despite rejection and the worst odds and it will be better than anything else you can imagine. Van Sciver’s work is almost entirely autobiographical in some aspect or another: He always leaves his “4 Questions” strip with a sentence that pertains to his life that week. But “Blammo” is unabashedly auto-biographical. Here, there’s no need for binoculars and dark night to peek into his apartment. No, “Blammo” is Van Sciver standing naked in your living room after not showering for the last stinking duration. “Blammo” is vignettes of a broken but convinced man quaking with conviction. Look at the lines he draws, they’re shaky. Melancholic. Unsettled. Broken. Human. Hearty. (W)hole. Van Sciver’s stories are simple. They are the collected Polaroids of a man shivering and shaking on a sunny day on the darkest beach you’ve ever seen. The stories are his everyday life, messy hair and bad breath and all. His stories and his comics are how he sees himself: honest and raw and as that awkward guy on the video recording or the voice on the answering machine. Van Sciver’s comics are the sounds of him cringing. They are of the face that those boys once punched in grade school. Yes, that face, the one that was so easily punchable, defeatable. Certainly, men like Robert Crumb and the late Harvey Pekar paved the way for underground comics all over the country. Films like “American Splendor” certainly popularized underground comics , but did they really? Cartoonists like Van Sciver travel the country, attending mostly invisible festivals and conferences held in out-of-the-way hotels and conference centers where they sit behind their tables like some elderly, washed-up wrestler. Then they slink back to whatever city they came from and crawl back into their drawing hole, their apartment. if you’re going to try, go all the way. there is no other feeling like that. you will be alone with the gods and the nights will flame with fire. The drawing gene has been in Van Sciver’s family for at least two generations. He never saw himself doing anything else, and now – nothing has changed. Admittedly, he is flying a bit under the radar that he wants to be seen on – still, he is: drawing, writing, creating – doing exactly what he always imagined. He cartoons for Westword. Kilgore Books in Denver loved his work so much that they offered to publish his work several times a year. And currently, Van Sciver has a deal with a publisher to draw a history of Abraham Lincoln and the President’s melancholic years of 1837-1842. Whether anybody else sees themselves in the gloomy drawings of Noah Van Sciver is probably irrelevant when it’s all said and done. For the victory in all those pages of “Blammo” and Westword have to undoubtedly be that Noah Van Sciver does become the hero of his own comics, and in the same laughing breath of air: The real victory in all of this is when Van Sciver sees, for himself, that he really has become a superhero comic book artist. Keep up with Noah Van Sciver’s unsettling future at: nvansciver.wordpress.com. do it, do it, do it. do it. all the way all the way. you will ride life straight to perfect laughter, it’s the only good fight there is. Poem in italics: “Roll the Dice” by Charles Bukowski |