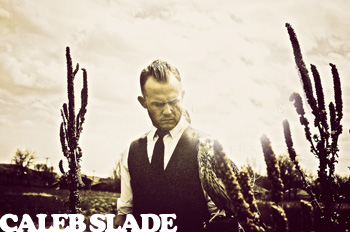

You don’t have to be afflicted to be affective. And you don’t have to be exhausted to be effectual. You do, however, have to be thoughtful. For there are bigger things out there – things that don’t really care if you stand or fall. Standing in the cosmic sandstorm: there is no force that will pick you back up. And so it is: the honest realism in the relationship of the unsympathetic universe to the solitary man. That sound, of a man swimming in his jelly fall to the ground and then bounding back upward – this is the sound of Caleb Slade’s debut album “Victory and Defeat”. This is an album about the difference in finding meaning in the world and trying to locate what is meaningful to you. This album, these songs – they are full of profound, lifelong meanings. For this album is about writing your story – and rewriting the myths of your life. For some, music is entertainment. For Caleb Slade, I have a feeling it is about a whole lot more. While there is much to say about what brought Slade to “Victory and Defeat”, what should be lauded is the sound: it is arresting. With the help of fellow musicians and engineers like Tim Hussman, Jeff Linsemaier and Nate Meese, Slade’s songs came to life with: Big arrangements. Strings. The stunt of creating false memories for the listeners by calling on history’s musical library. The production is dreamy and voluptuous. The songs are both accessible and soaked in sensualism. At times, Slade’s songs drip with a surreal symphony of sound. A true wall of water. For a listener familiar with the last thirty years of pop music and that found obscure: pockets of comfort are to be heard and felt in and among the wavy surges of self-assurance and it’s battling counterpart of standing in front of the mirror, naked and beyond your strength, older than you thought. Slade told me: life isn’t a dress rehearsal. Stand up. Dust yourself off. Think straight, long, and: rationally. Be active. Not standing on any stage outside of his sternum, Slade willingly stirred-up the dust storms he has seen. Some of them, anyway. Raised in a home of Christian missionaries, Slade lived a bit of an unorthodox childhood – in the states, in Guatemala. He went abroad to study in Switzerland at a shelter of intellectuals that encouraged him to stray away from the median, from the Christological teachings his life found its fundamentals in. There he stared long and hard into the mirrors of mysticism, self and spiritualism. Slowly, certainly, with deliberate picking and seeking – those clothes fell from him. Slowly, then suddenly there he was: naked and without a narrative to explain himself. The story he had grown to value as both shield and sword, folded and dissipated. That meta-narrative that he had fit so neatly into before – was now gone. Brave, do tell: When a man loses the narrative that has served as fuel for meaning and purpose, what is he left with? Answer: The courage to walk on, or nothing. Answer: Himself, or nobody. This is the story of anything great ever won: take a risk, use your senses, find resources, lean on what you can – get through today and begin to build something beautiful, even if you can’t remember what beautiful is. Because don’t you dare drown here: for this was your choice. It always will be. Possibly this was the biggest choice that Slade has made in his short life. To walk alone, and to create a new narrative to explain your existence is a brave route, no doubt. Sometimes, it can prove foolish. Luckily, Slade has the skills needed to design some new clothes for his new frame of a human house and his new story. Blessed he was: For after returning from Switzerland he could have gone a couple different routes – possibly even to law school. Instead, he put to work his affinity for lateral thinking and left-brained tasks like logic in an undergraduate degree in philosophy. And: towards being a musician. For it is here where music may be the solution to so much: for the oftentimes stoic Slade, his on-stage performances are monstrously cathartic. For Slade, music has become a place to explore his emotional life, his emotional self. Maybe, just maybe: this is his new alter, his new chapel, his new schoolroom. For somebody like Caleb Slade, formerly a football player and car repo man, one not a stranger to confrontation - music may be the panacea. The grand problem solver, music tests an artist’s memory in the same way it employs the left-brained, problem solving side just as much as it draws paint from his creative, right hemisphere. Evidence of his marriage of aptitudes could most easily be seen in his strange habit of not writing down songs until they’re finished. Working on the premise that he will remember the good songs, the strong parts – those that possess some kind of resonance and long scale frequency – Slade has termed his process and method, “Guerrilla Piano”. At the end of the book, it is Caleb’s story. And while the story is still unfolding and while his truths are still finding their legs – an examination of Slade’s debut album may provide our first chapter. For what you can see and hear, in his process and in the final product, is the tale that this was about learning his lessons: as a songwriter, as a musician and as a man. Where Slade found comfort and trust in his mentorship with people like Hussman, Linsemaier and Meese; and where he wanted their extraordinary talents to shine through in his work – Slade came to see himself as a strong songwriter who can produce dense, melodic lyrics. Standing next to men that he admired, he saw himself growing in the mirror: that his pen and voice was strong enough to emote the bigger things that were swirling inside him. Here lays the story of a man that found victory in defeat. Here lays the sound of humility, optimism in the notion of choice and the elimination of topical assumption – both about him as a man, and about those ideas and people all around us all. This is but the beginning. Listen to Caleb’s future here: www.calebslademusic.com |