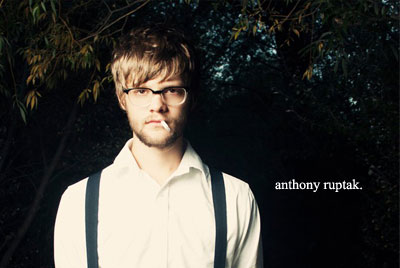

Song is story. Story is song. Before you can become the hero of your life’s novel, you must just earn a spot as a character in that story. Fortunately for Anthony Ruptak and his early twenties tales, he penciled himself in the role of the imaginary boy from the western woods a long time ago and like a mountain fern, he let it grow. It all began in this earthy pocket of life: as a boy, in the forest, running free, nearly invisibly – save for the carvings in the trees and the Bailey-wood films that he and his brother starred-in. Anthony was taken out of public school by the second grade. He was raised in a deeply pious home, full of music. By day, into the night, he and his brother wandered the woods. At eleven he was given his first Squire. He was as he still is: his only music teacher. At thirteen he was playing worship music in church. Since he was sixteen he has worked full-time – the same age that he left the church and began to rebel by screaming his own brand of music. A year later, he moved-out of his parent’s home. Ever since, Anthony has been oddly on his own. Yes this is all pertinent. Because: Song is story. But, you don’t need me to remind you of any of this. Just listening to the bearded bard will give you the hard truths that you really need to know: he is not completely on his own. He has his stories - his family. His parents guest-star in many of his tales. His dead dog makes an appearance. So does the church and its parking lot, with his bicycle. The first elk he killed in in there too. And: his good heart. I’m not certain if it was the movies or the woods. I’m not certain which began to write his character’s dialogue first. I’m not certain where the music came from. But I think Anthony is remembering. His songs are like combines. Upon ignition the teeth and the gears begin churning and he just throttles it out and into the open – tearing up the fields, raping the land of its bounty and leaving the earth bare and naked and ashamed, but somehow grateful. And Anthony sings backwards into the afternoon, over the land. Anthony’s latest creation, “C'est La Vie” is one of the strongest songwriter albums in the Queen City, in recent times. And has he worked for it: No open stage in this dusty town doesn’t know his name – he has been the Argonaut in this journey. He has taken it personally and paid his dues (sometimes four mics in a night) – but he still has some money left, to give and to earn. On this, his second full studio session, it’s apparent that this Coloradan understands something about the role of folklore, the sense of song and how he commands his work and his stages. In front of an audience, Anthony’s control and execution is polished. His hands are unshakeable. Sometimes his sets feel like a conversation that is near to the end, just before bed. His intensity in pace and diction is alarming – arresting to any pair of ears hearing his water-shaken arcs of story. And yes, young Anthony is right: he does have an old soul. It’s autumn and it’s raining and he says things to me like, “primordial purpose” and “veiled introspection” – as though he has thought about what those things mean. He alludes to something being pejorative, like a “vaporous zephyr that is pulling you to your end” as though these words too were born inside his mouth. He speaks as though his lexicon lives in the same world that I inhabit, just a bit more to the west; up in the hills. We are outside, smoking cigarettes. I am soaking wet and so I take off my glasses but he doesn’t take his off and he is talking to me and I am thinking about how his music sounds like this rain that is soaking me but impossibly, not him. He says things like he owns every episode ever made of M*A*S*H and I have never heard anybody say anything even remotely close. He smokes his down to the nub and flips his still-dry hair out of his eyes. I think this is what happens when you live your childhood out and in the forest: the rain means something else than it does to the rest of us. Anthony’s music is a bit like this: like a conversation in the rain. Sometimes he has to shout because water can be loud. Other times, he has me under his pen, under the phrases and stories he has carried with him like he hasn’t any other belongings but these words and journals. And stories – they’re like tales dripping from his beard. His songs take place in real places. In this world we all know. White tail doe in the back of a Chevy/ She was stiff and warm and her blood flowed heavy/ We dropped her body at the edge of a clearing/ And I got wasted in the golden evening There is something about Anthony’s songs that always turns to the hunter. There’s the elk in “Poacher”. His old dog and the grassy graves. His glistening bones. He talks about animalistic time. In his musical tales there’s always some kind of movement, a pace, a wordy rhythm – just like his conversation when he gets excited. It’s like he’s always, always moving through the woods, stealthily, through the grass: hunting, aiming, wanting, needing. If you see him on stage and it makes sense: he carries himself like somebody you should listen to, like he has hunting stories for you to hear. Where the protagonist becomes the hero is deep inside, somewhere in the guts. It’s in here where the story turns. Anthony’s road has been a corduroy one. He has had to find his place in a world full of forests, when he is not, in fact, one of the trees. He doesn’t sound like them. He doesn’t talk to the other trees like they do. He didn’t go to their school and doesn’t have any desire to know their emphasis of study. Still, Anthony has lived among them. Sure, some of those times have been in his car. Alone: with his suitcase of stories, his good heart and his will to keep telling tales, writing songs and playing music. In an electronic world, Anthony finds gratification in his analog cabin of rifles, rung guitar necks and stuffed, mounted heads and stocks. Even as close to the city as he will probably ever get: I can’t imagine that his home doesn’t smell like woodsmoke and lapels. I first met Anthony a couple of years ago. He didn’t really know any of the players in town. While he was reverent to their presence, he didn’t seem concerned to either know these people’s names or not. Now things are a bit different. He’s being asked to play the shows that matter. He’s writing even more mature work. He is exerting his bravery and abandoning any possible throes of contentedness. It seems that in his primary occupation of uncovering the poignant fictions of his life, Anthony Ruptak is somehow creating a reality of his own – one that is predicated on what he has to give, his belief in what song means to us as beings and all of these earthen stories of naked, broken and beautiful life. |